Bacillus anthracis

TAXONOMY

Domain: Bacteria

Phylum: Bacillota

Class: Bacilli

Order: Bacillales

Family: Bacillaceae

Genus: Bacillus

Species: B. anthracis

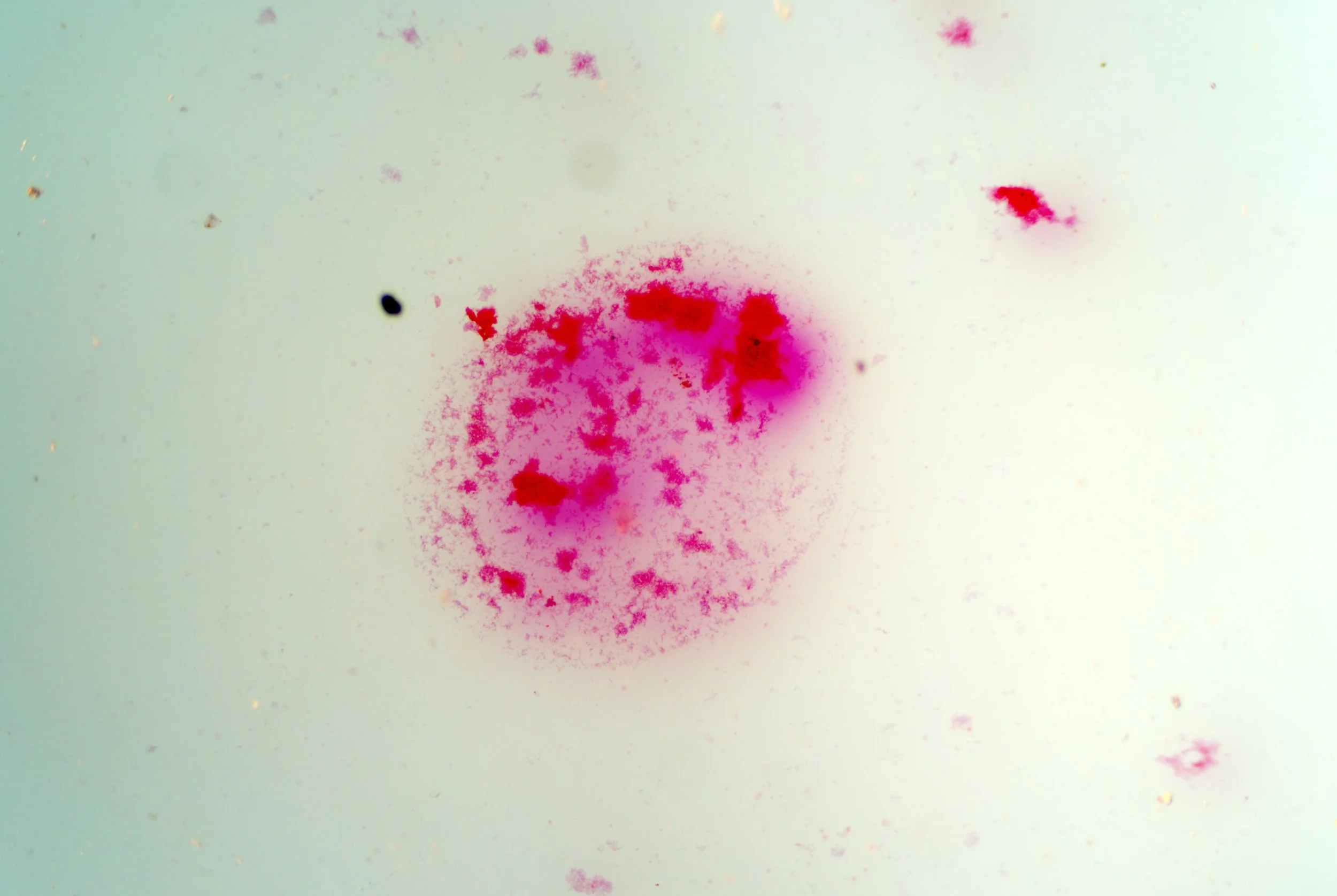

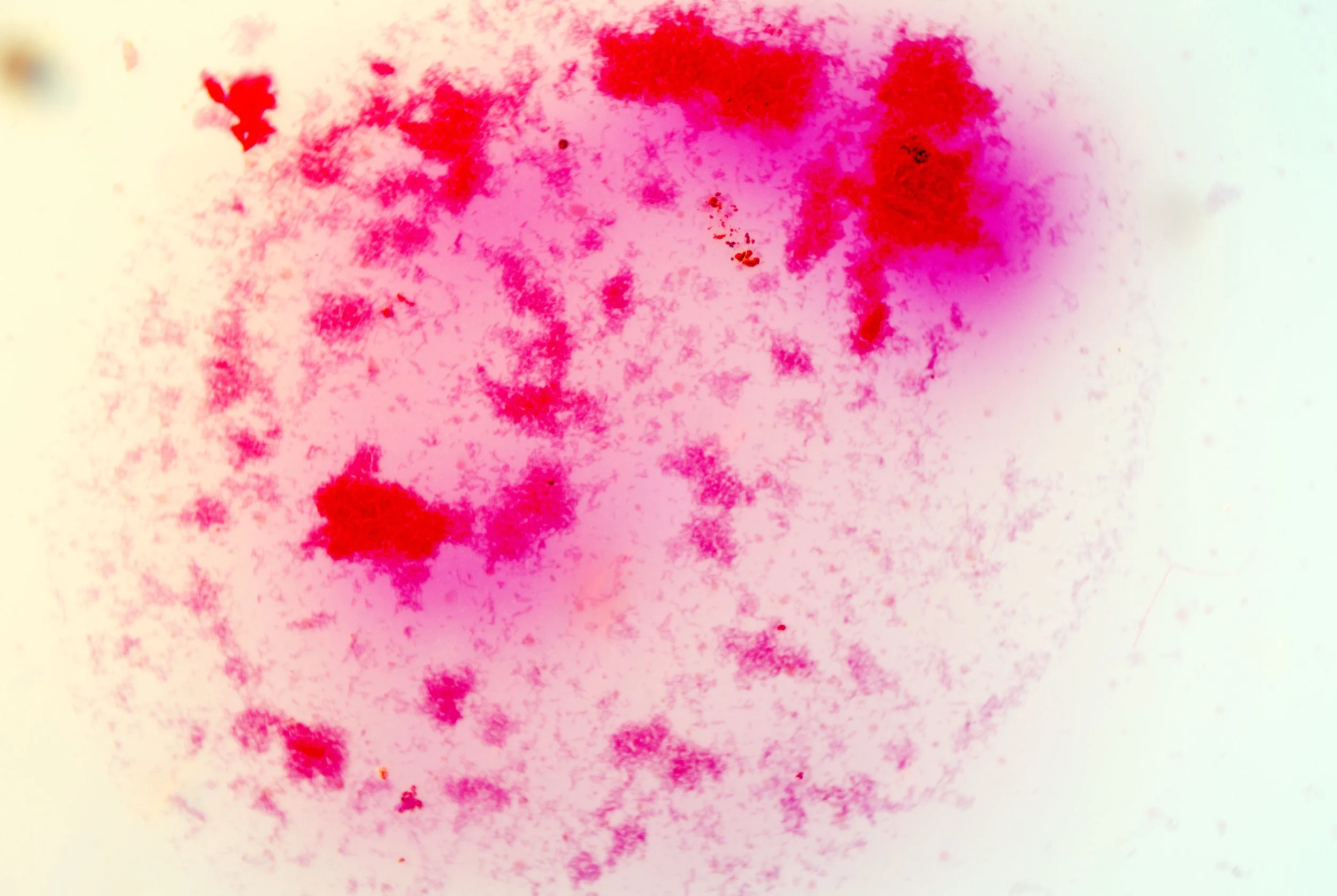

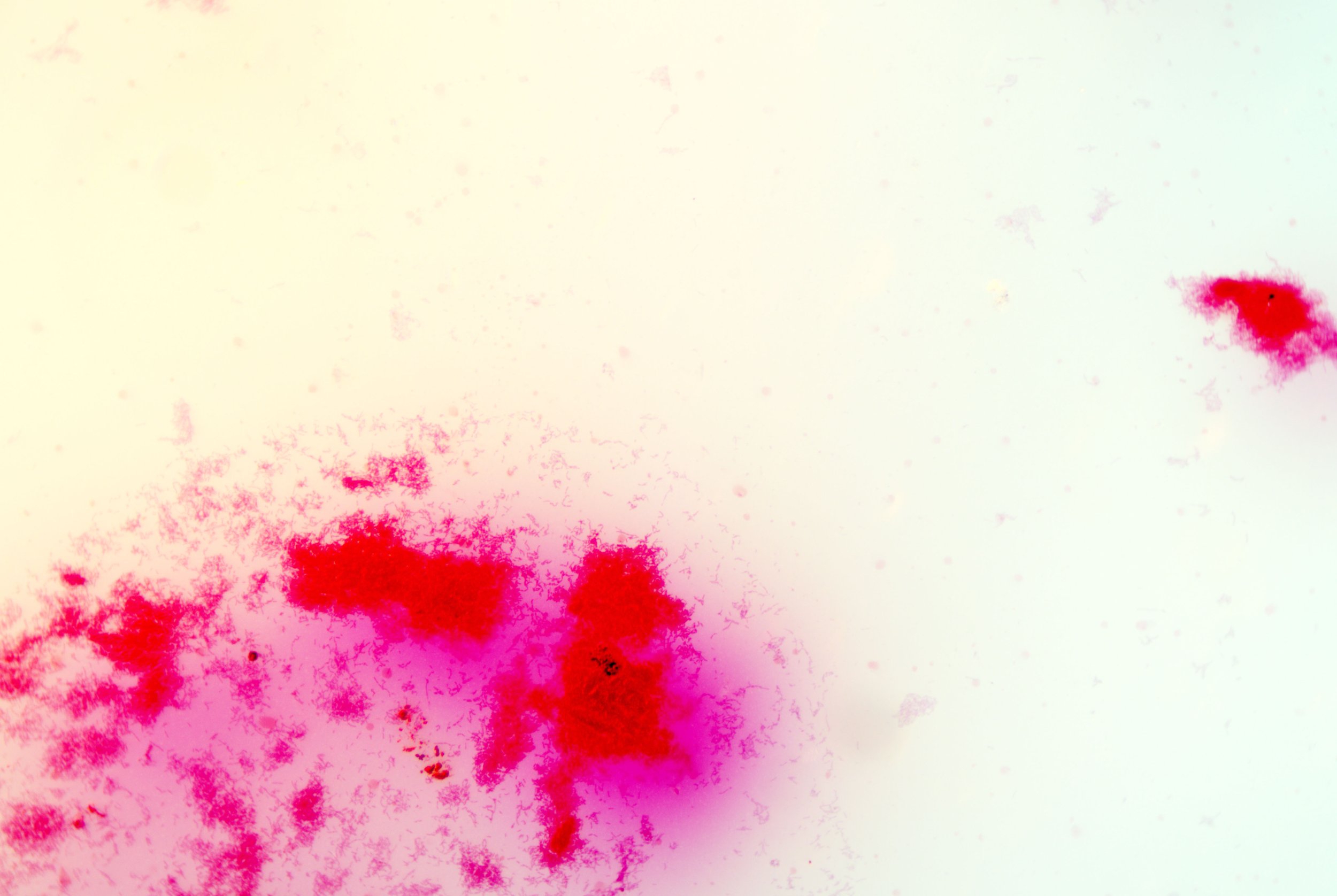

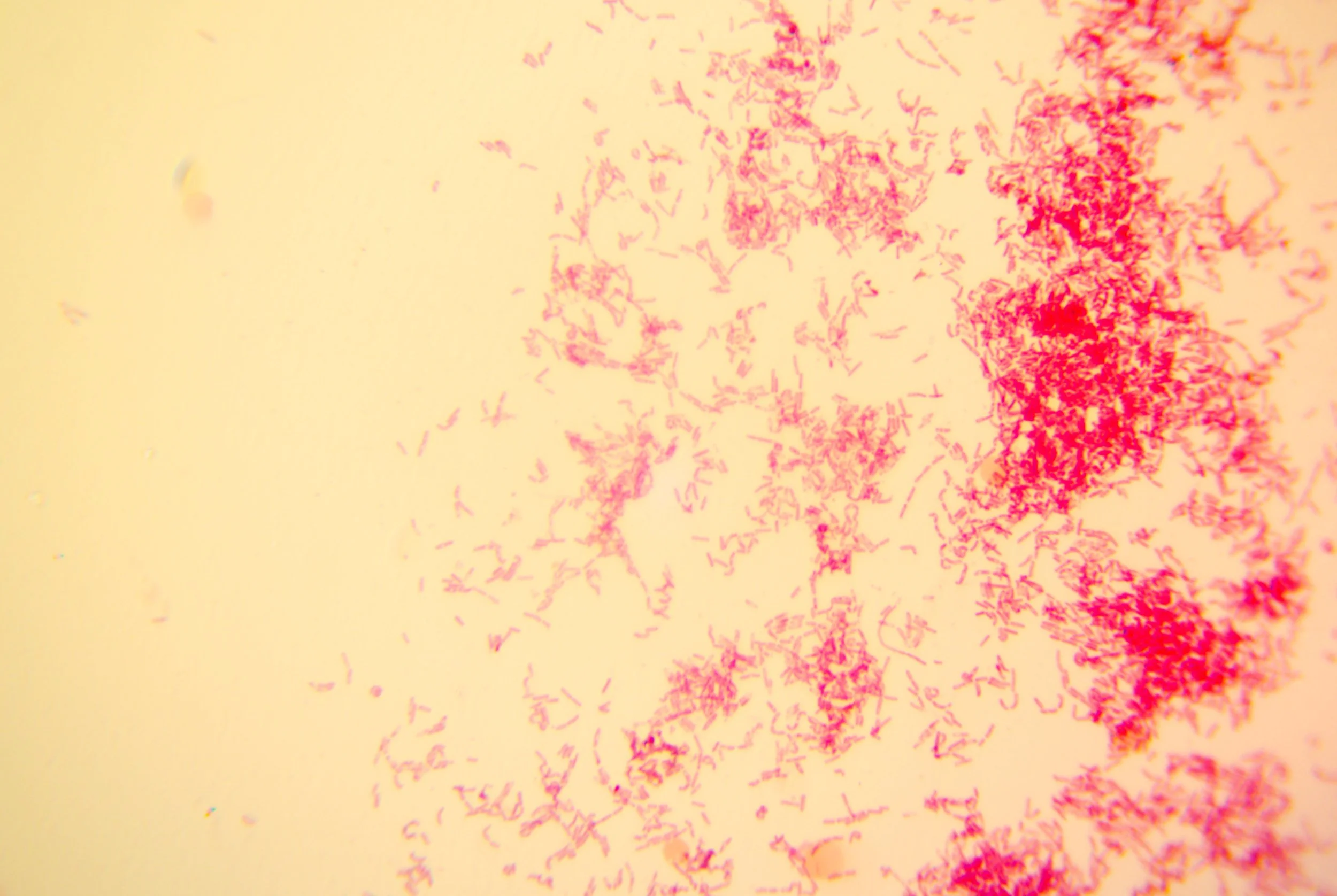

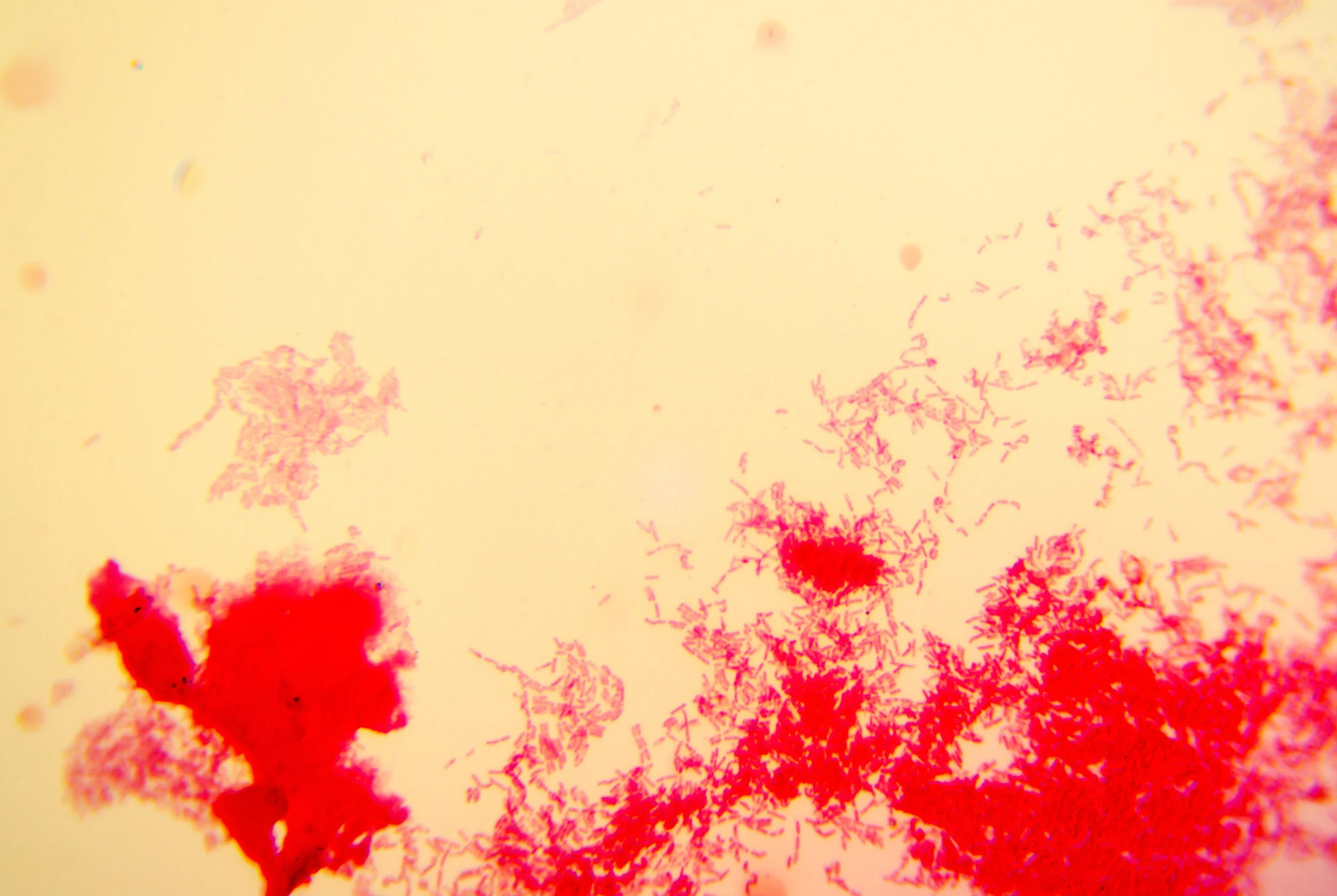

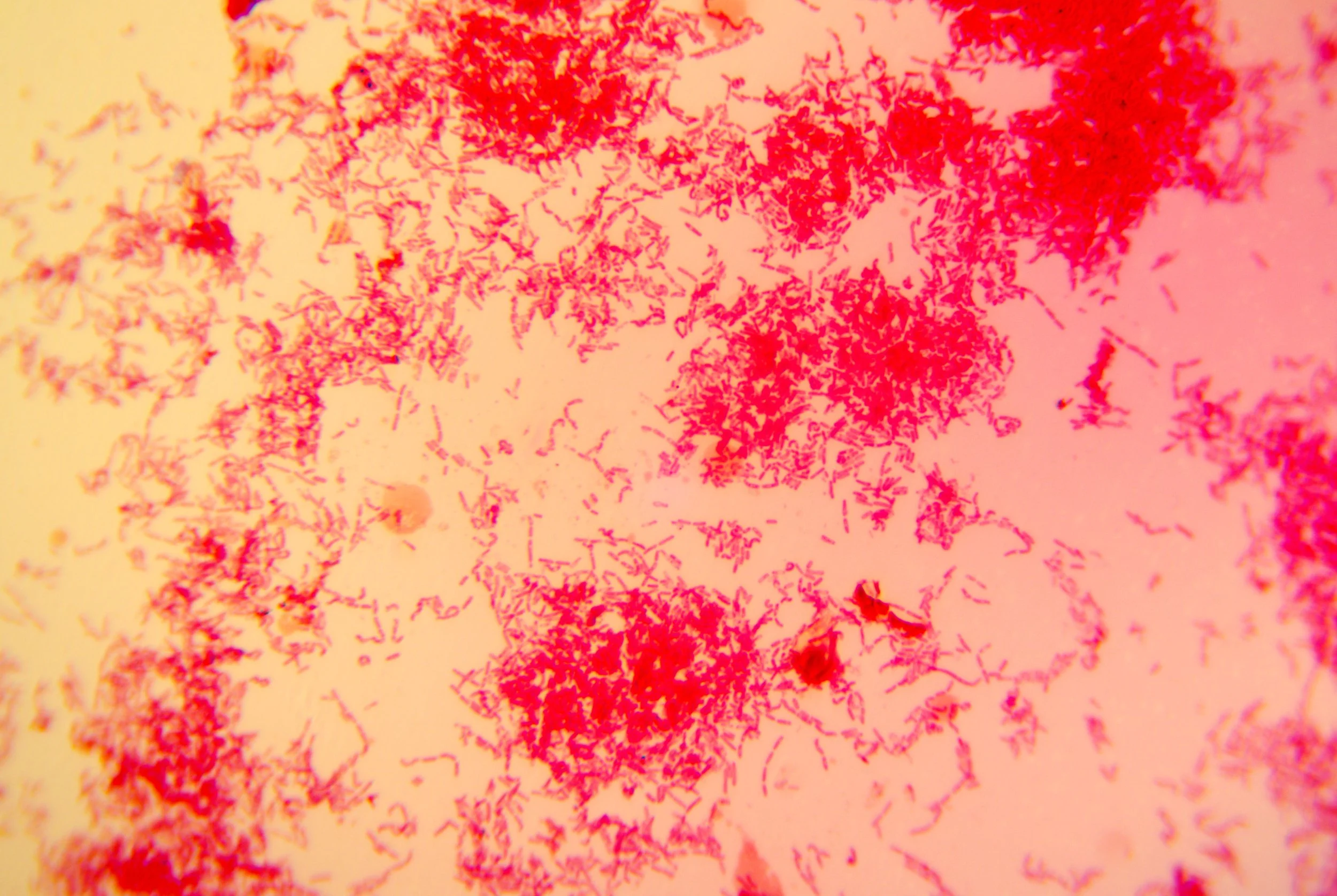

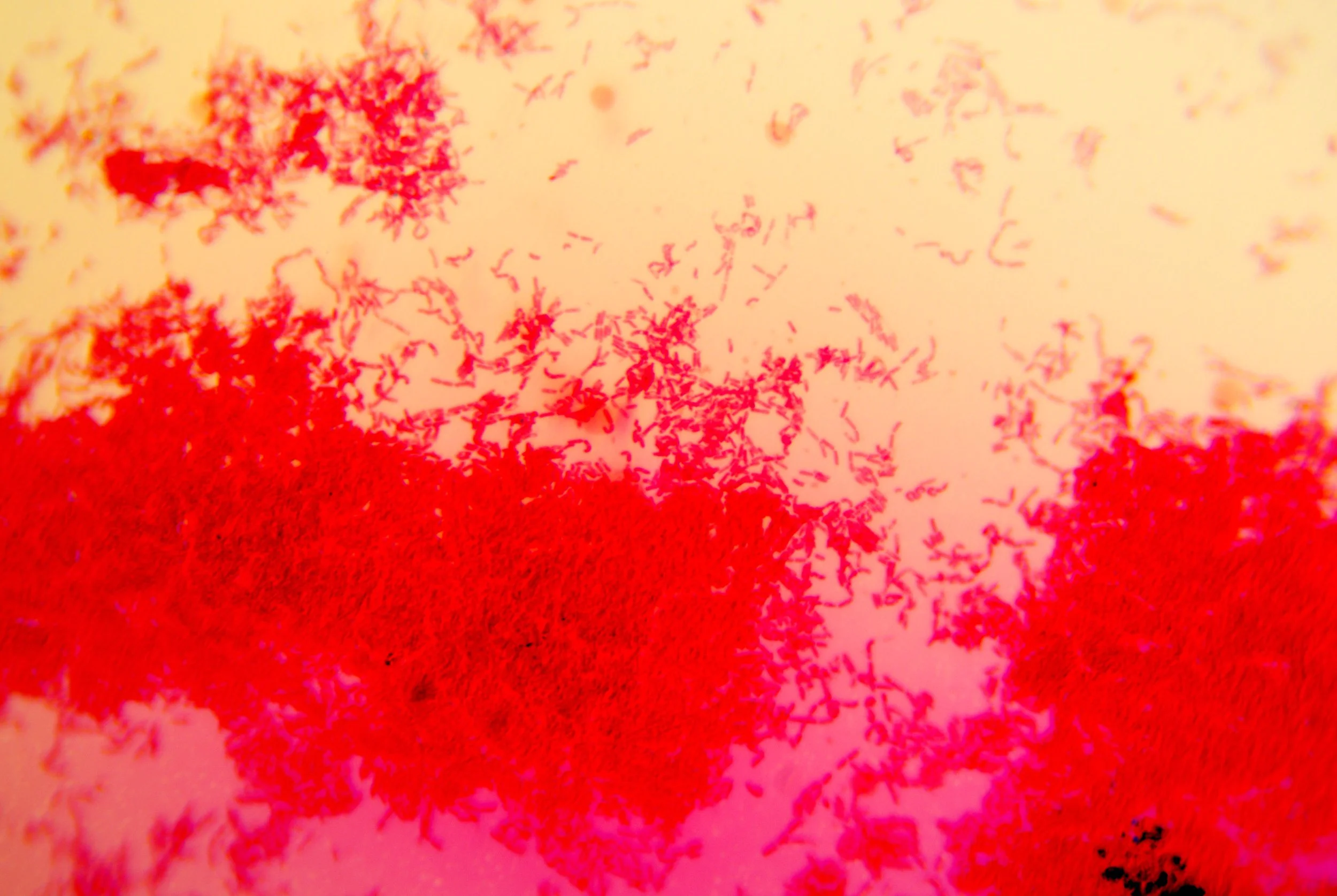

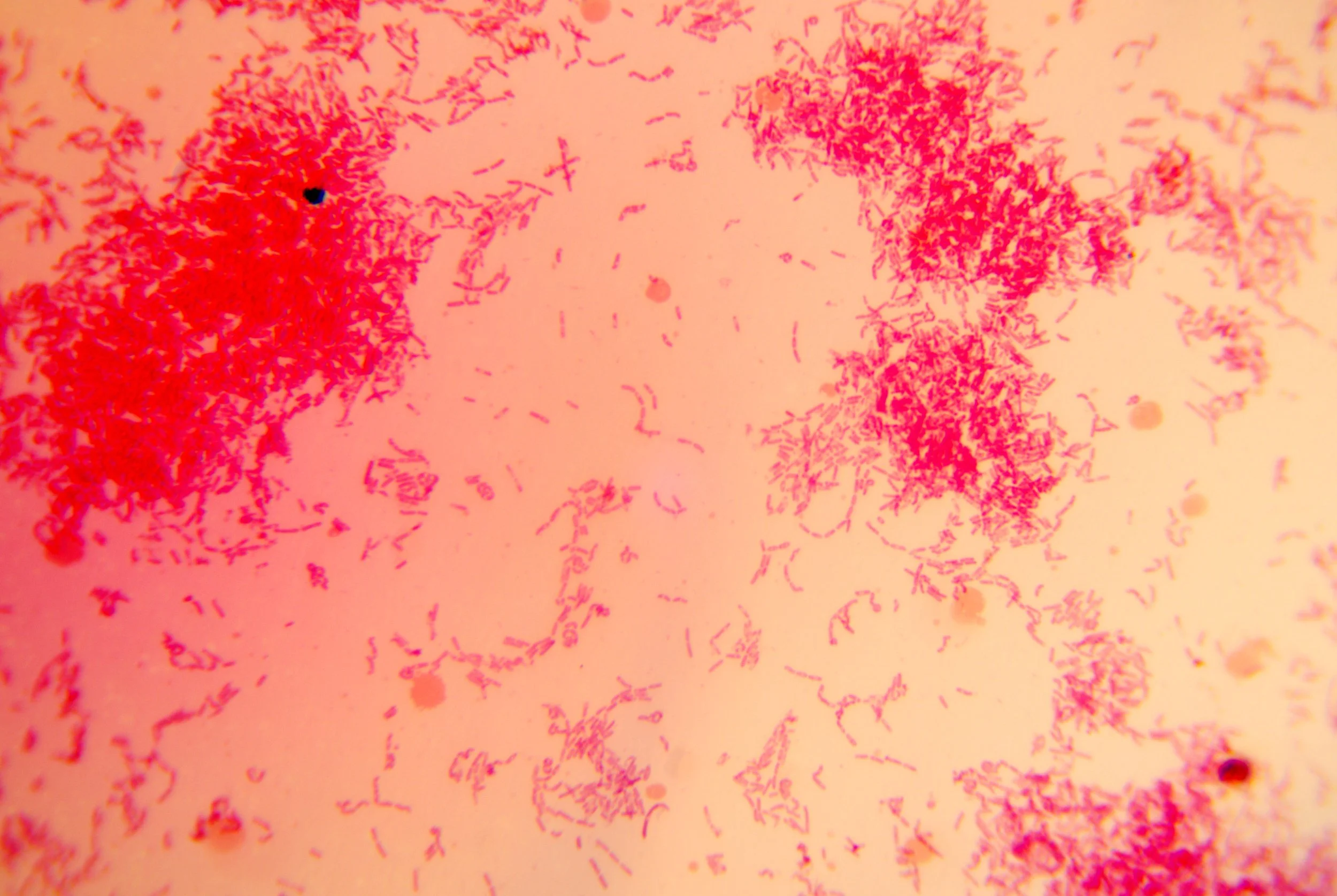

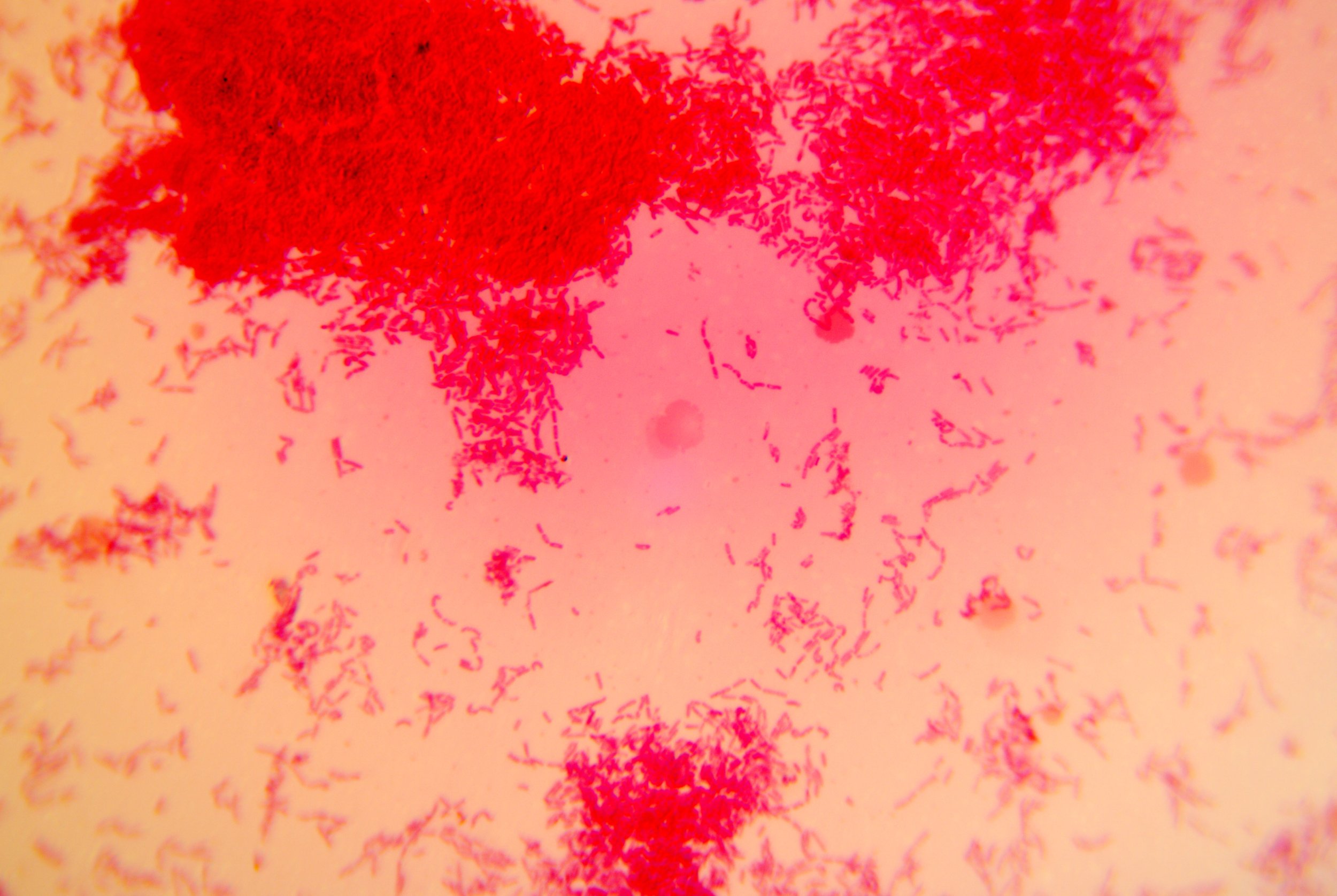

MORPHOLOGY

Gram‑positive, rod‑shaped bacterium measuring roughly 3–5 μm long and 1–1.2 μm wide

Forms long chains with blunt ends often described as “boxcar” or “bamboo stick”; colonies on agar are large, white or cream, and slimy due to the capsule.

Each cell forms one oval, centrally located endospore; spores are extremely resistant to heat, cold, radiation and desiccation.

Requires oxygen to sporulate and produces a poly‑D‑γ‑glutamic acid capsule around vegetative cells that shields it from phagocytosis.

Spores can persist dormant in soil for decades, emerging only when conditions are favourable

NOTABLE TRAITS

Virulence depends on two plasmids: pXO2, which encodes the capsule, and pXO1, which encodes the tripartite anthrax toxin.

Capsule: composed of poly‑D‑glutamic acid; helps the bacteria hitchhike inside macrophages and inhibits phagocytosis.

Protective antigen (PA): an 83‑kDa protein that forms a heptameric “prepore” on host cells, serving as a gateway for the other toxin components.

Edema factor (EF): an adenylate cyclase that raises intracellular cAMP, disrupting cytokine secretion and causing oedema.

Lethal factor (LF): a zinc‑metalloprotease that cleaves MAPK kinases, shutting down immune signalling and triggering apoptosis of immune cells.

Feeds on the heme of haemoglobin using secreted siderophores IsdX1 and IsdX2.