Clostridium tetani

TAXONOMY

Domain: Bacteria

Phylum: Bacillota

Class: Clostridia

Order: Eubacteriales (Clostridiales)

Family: Clostridiaceae

Genus: Clostridium

Species: C. tetani

MORPHOLOGY

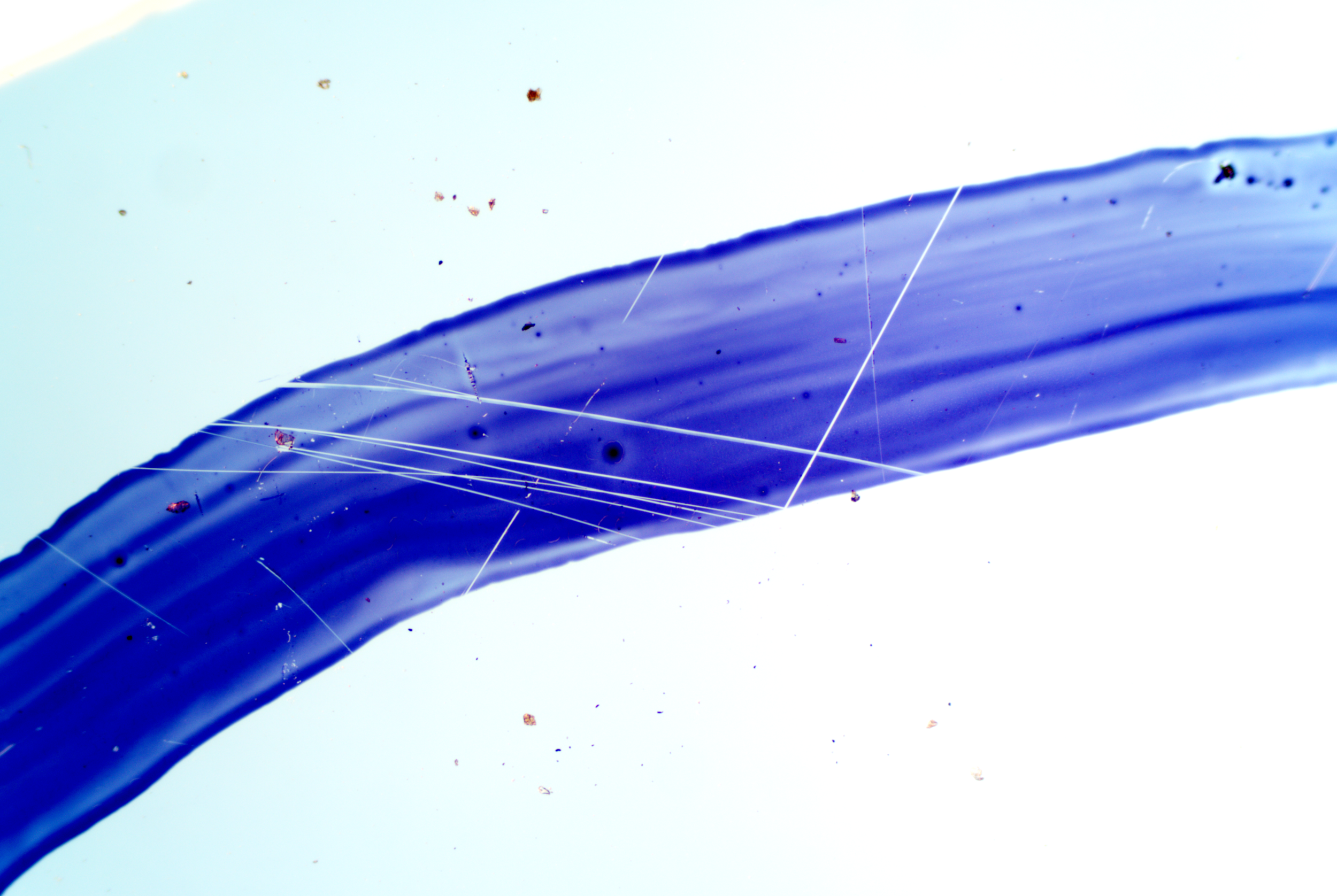

Slender, Gram‑positive rods typically 0.5 µm wide and up to 2.5 µm long.

Obligate anaerobe; cannot grow in the presence of oxygen.

Motile via peritrichous flagella, which are shed during sporulation.

Forms a single terminal spore that gives the cell a distinctive “tennis‑racket” or “drumstick” shape.

Spores are extraordinarily hardy, resisting heat, antiseptics and boiling; they persist for years in soil and animal intestines worldwide.

Vegetative cells stain Gram positive in fresh culture but may become Gram variable as they form spores.

NOTABLE TRAITS

Causative agent of tetanus, a disease characterized by painful muscle spasms and “lockjaw.” Infection occurs when spores contaminate a wound and germinate under anaerobic conditions.

Produces two toxins: tetanospasmin (tetanus toxin), one of the most potent toxins known (lethal dose <2.5 ng/kg), and tetanolysin, a hemolysin with unclear function.

Tetanospasmin blocks the release of inhibitory neurotransmitters glycine and GABA at motor nerve endings, causing sustained muscle contraction and autonomic dysfunction.

Spores are ubiquitous in soil, dust and animal feces and are not transmitted person‑to‑person; infection arises from contaminated wounds.

Tetanus is preventable through vaccination; inactivated tetanospasmin (tetanus toxoid) is a core component of DTP/DTaP vaccines worldwide