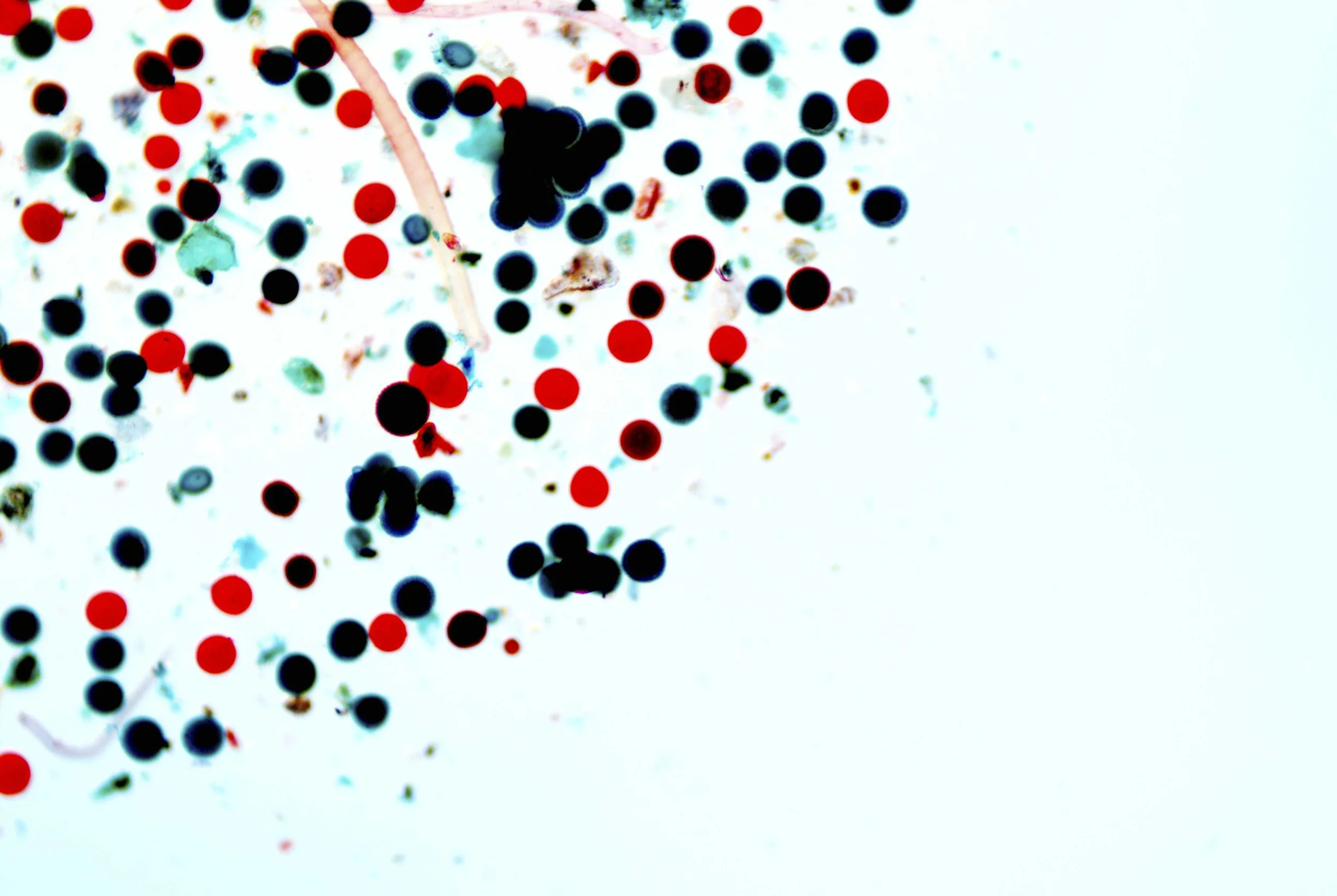

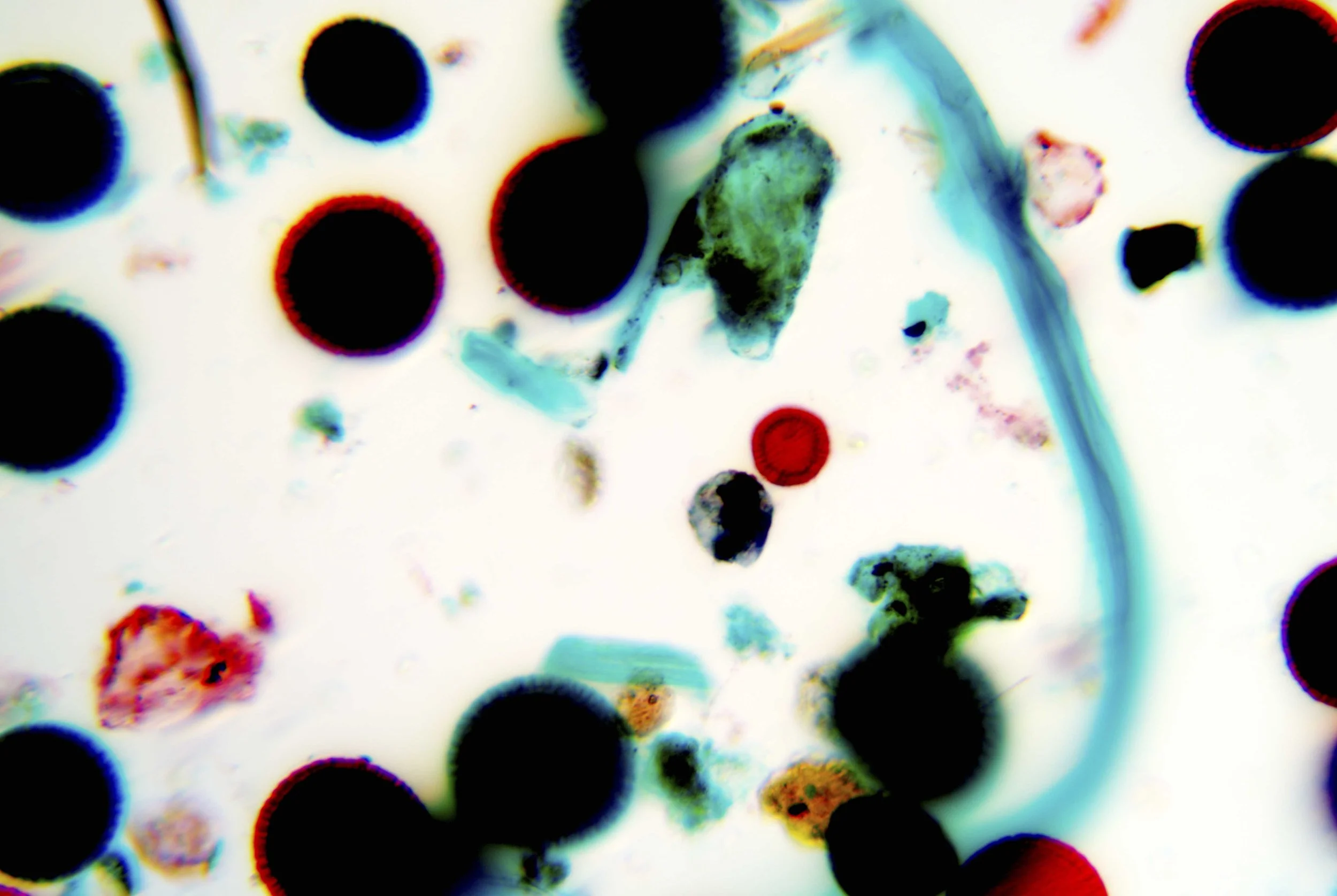

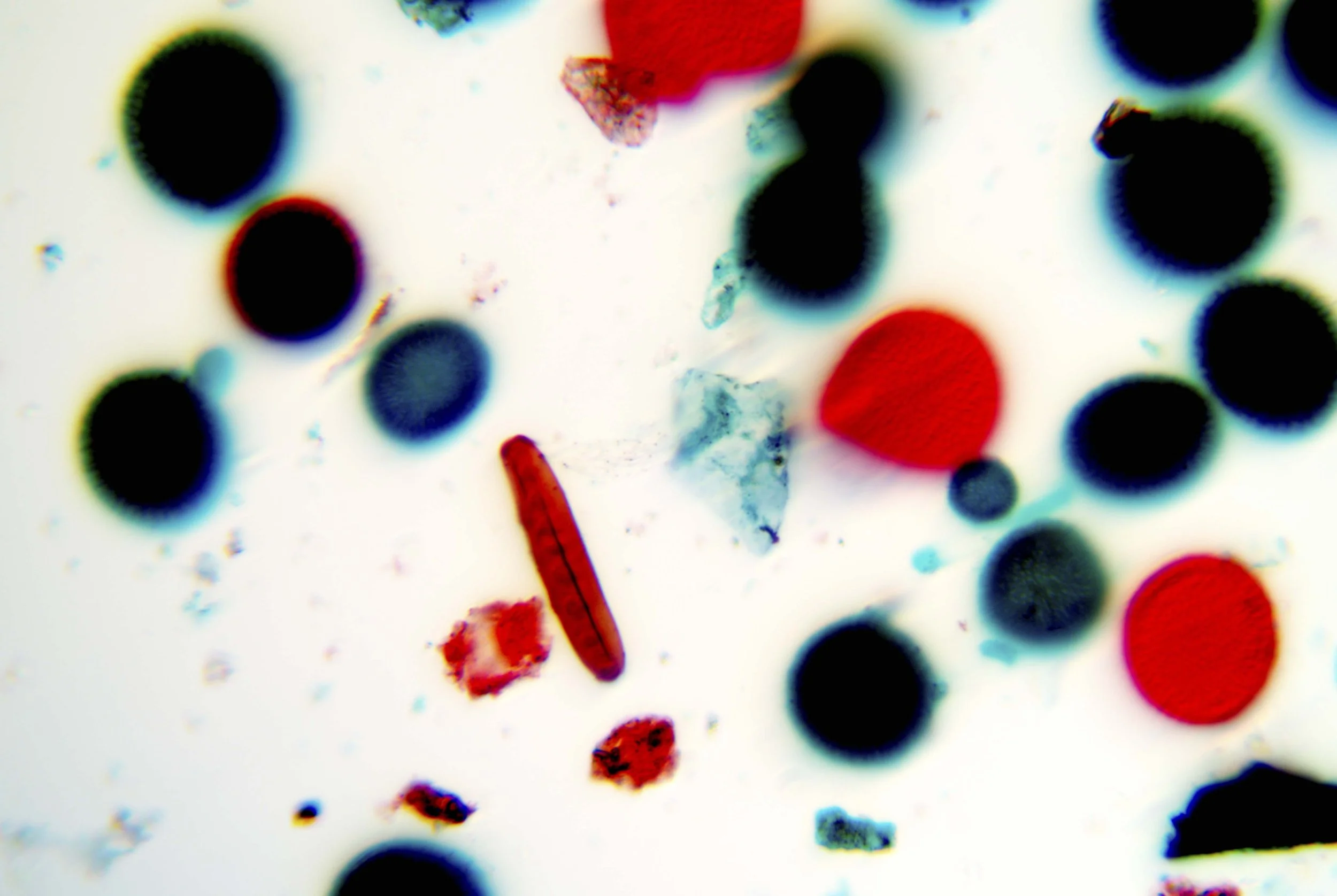

Despite their tiny size, pollen grains are among the most structurally diverse cells in biology. Their surfaces are covered with ridges, pores, spines, or smooth shells depending on the plant species, architectural features formed from sporopollenin, a biopolymer so resistant and durable that it is considered one of the most chemically stable substances found in nature.

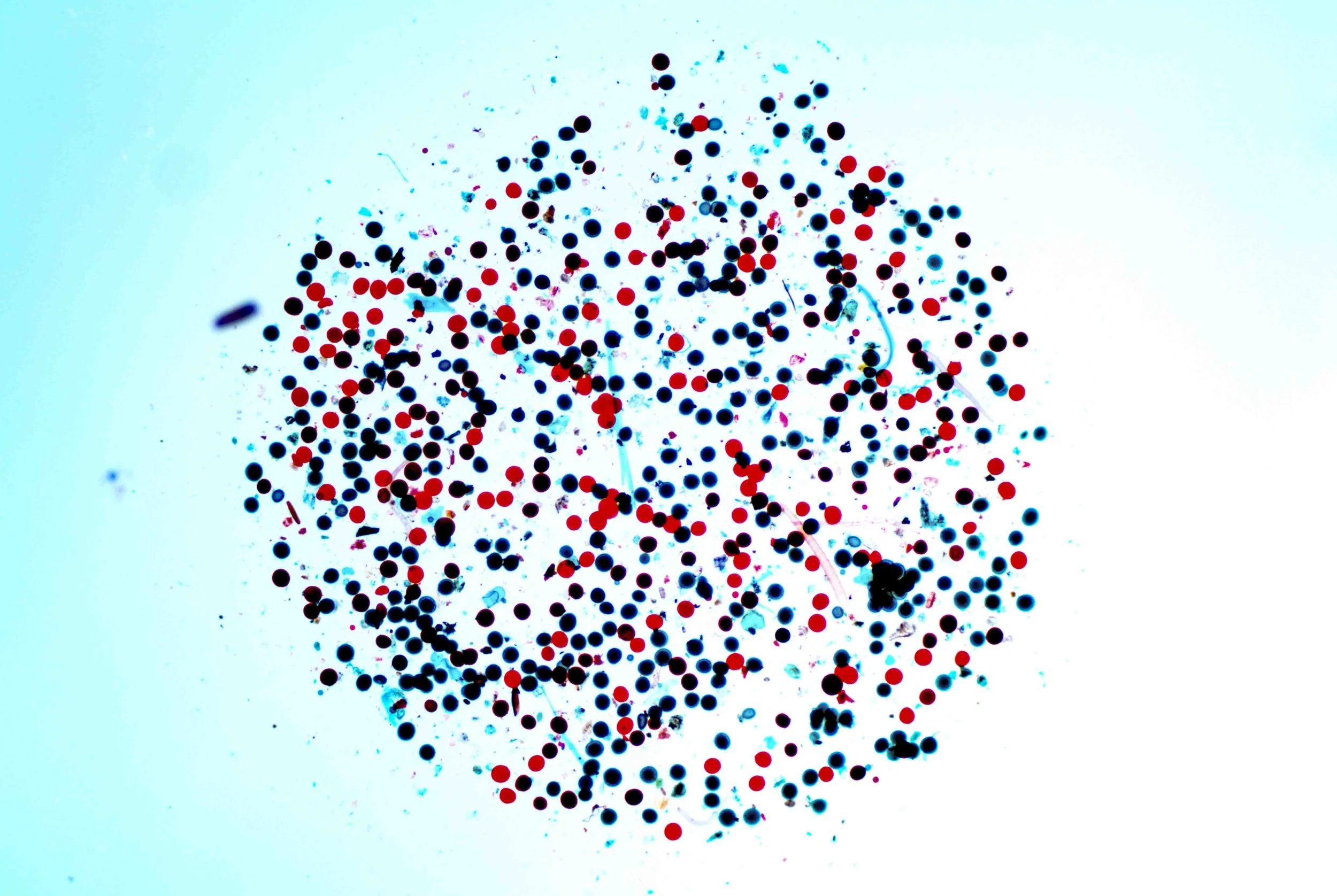

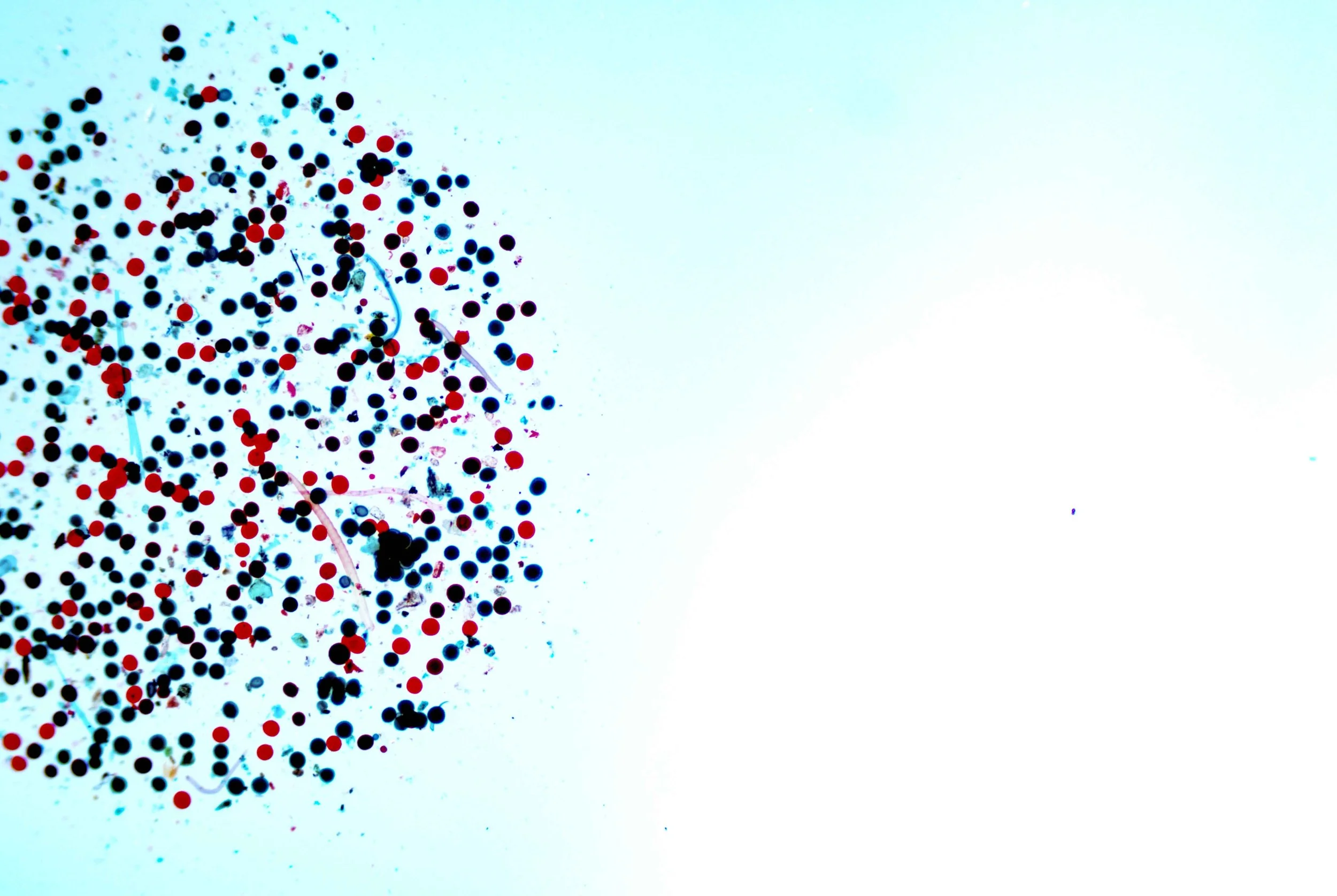

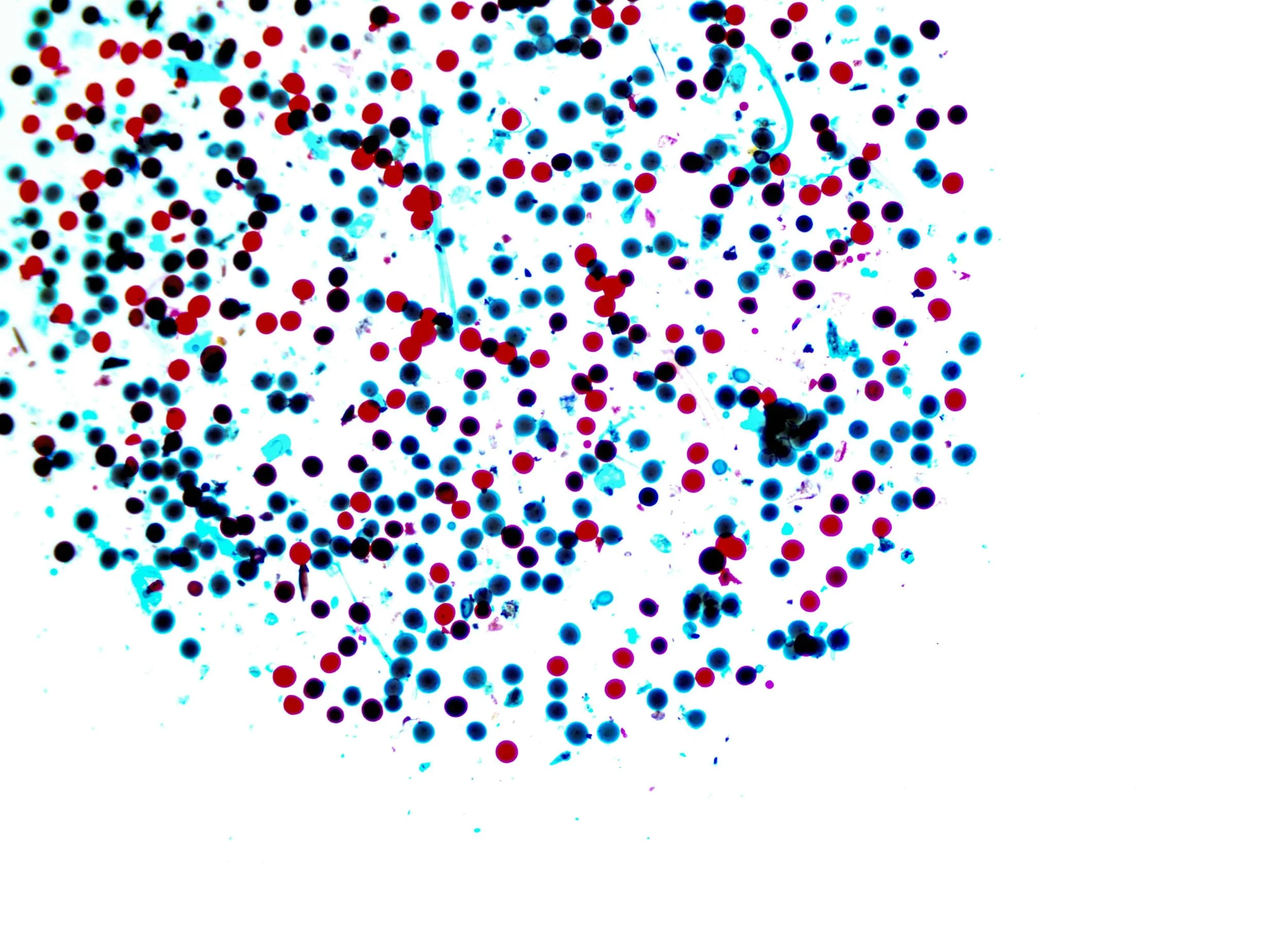

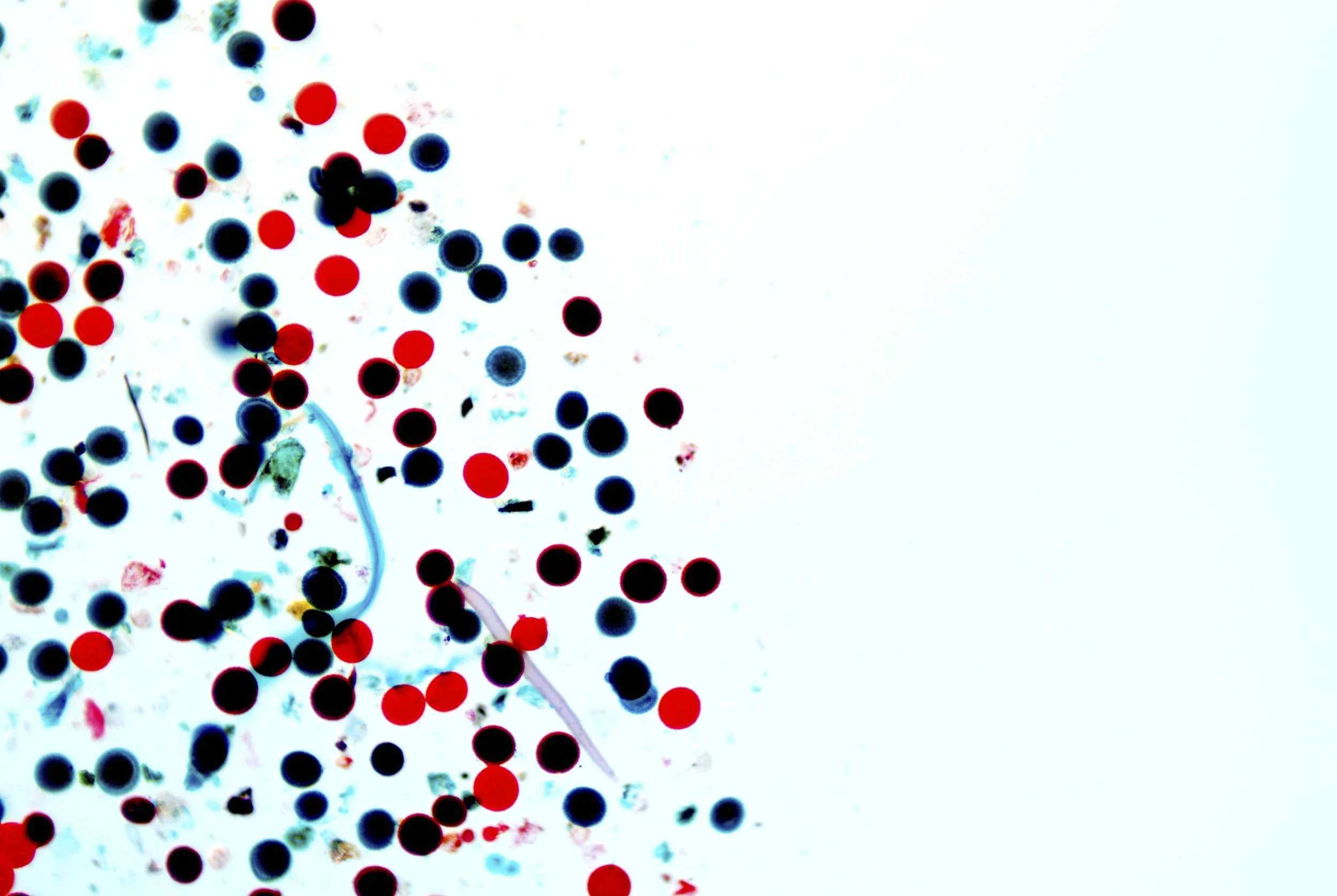

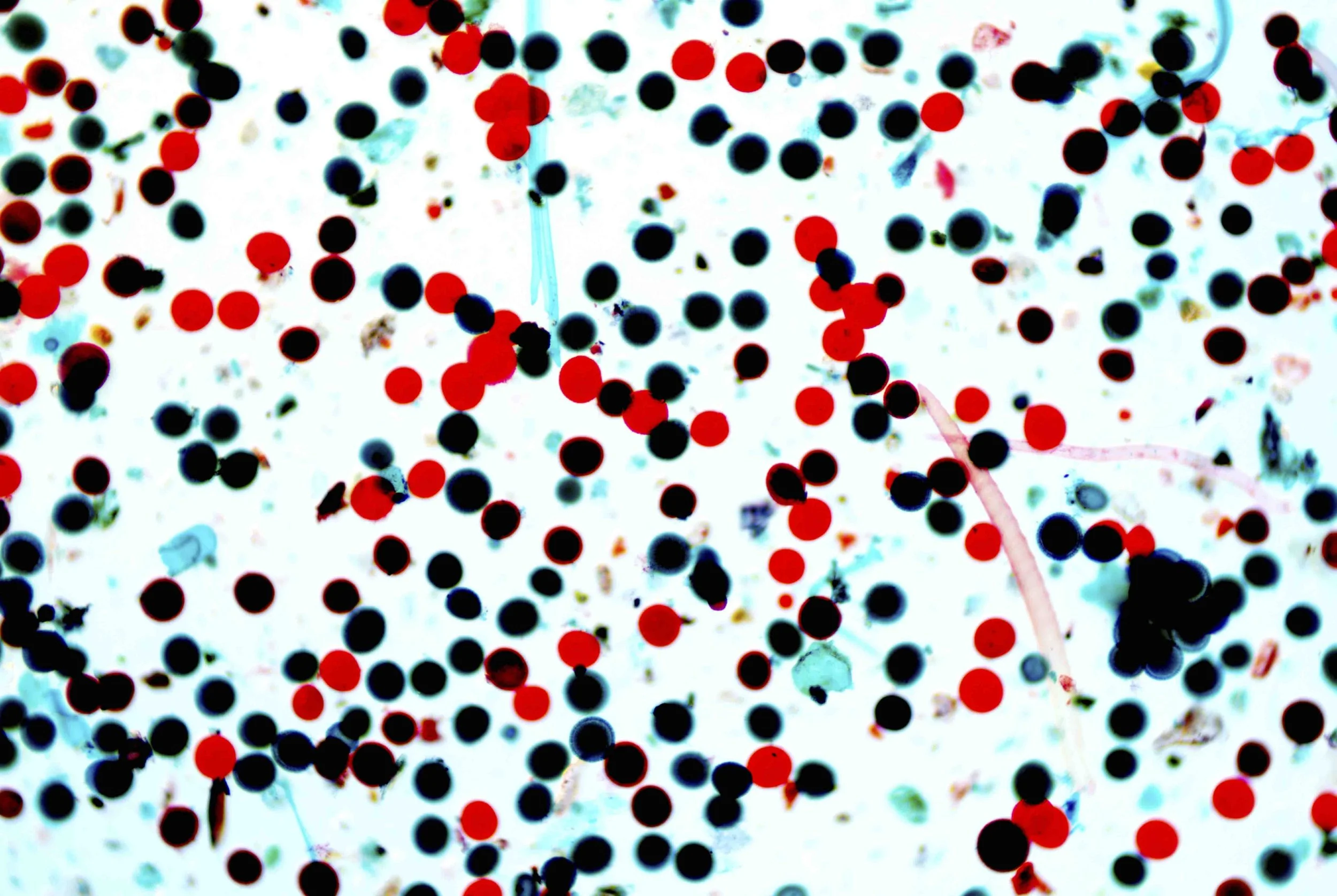

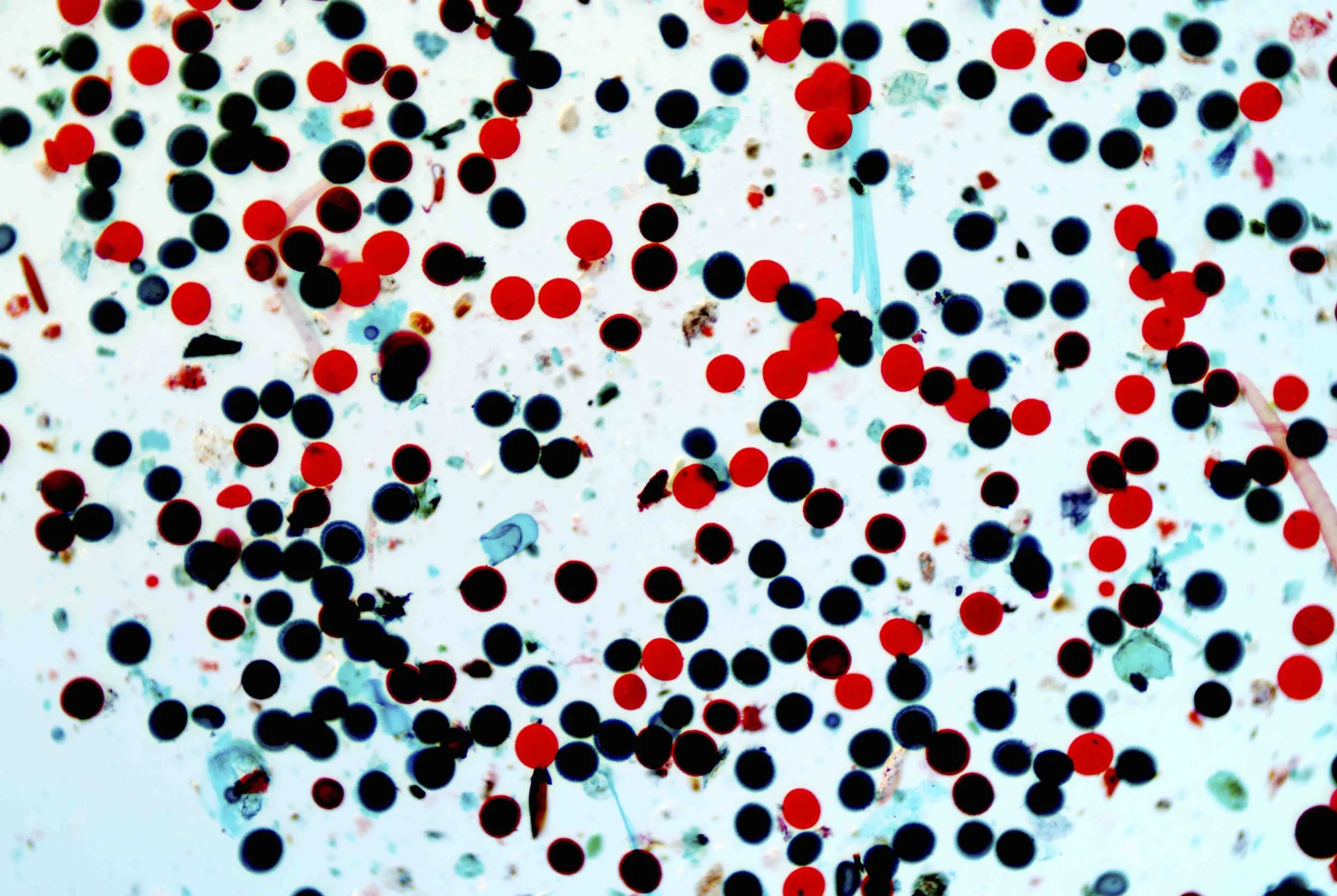

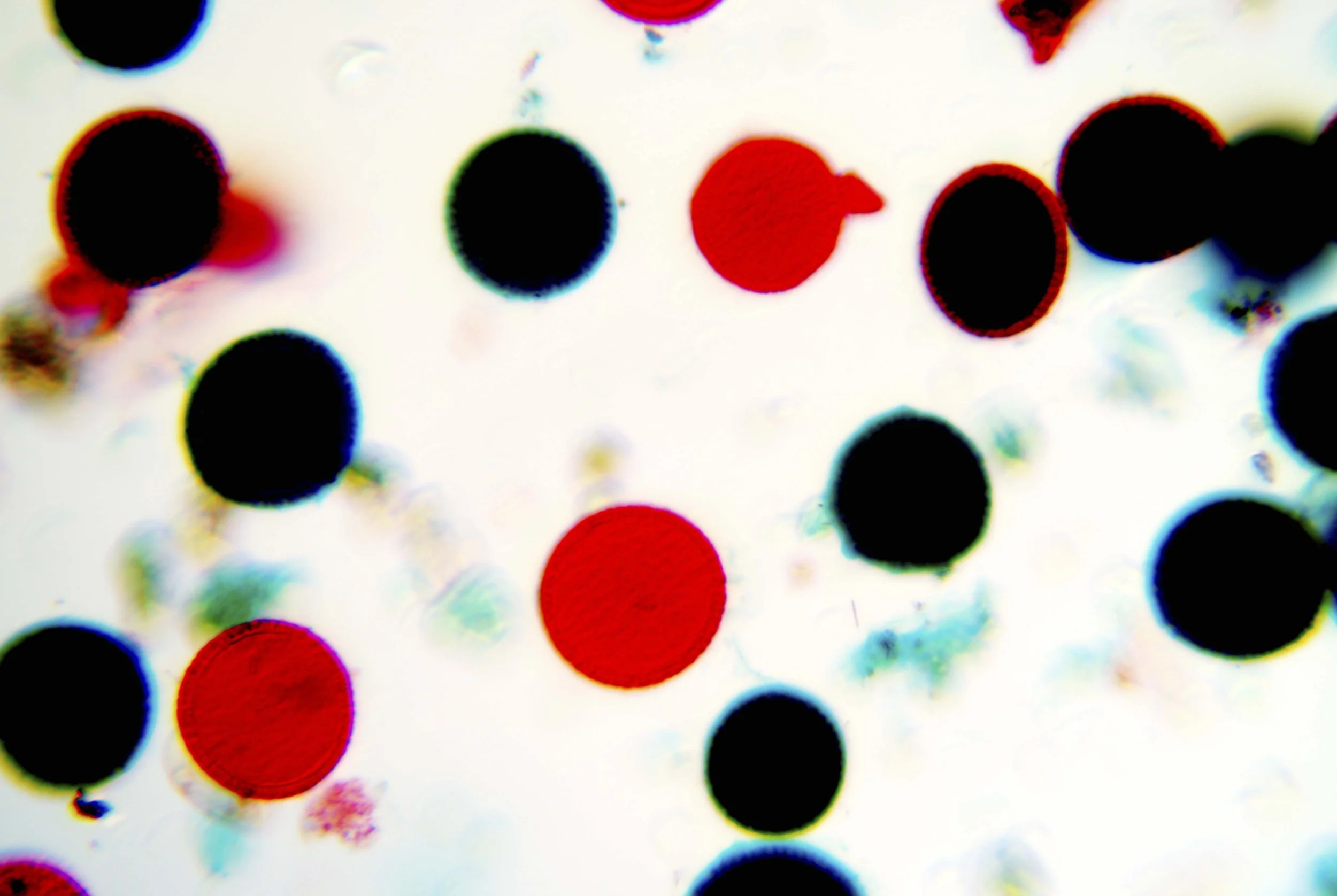

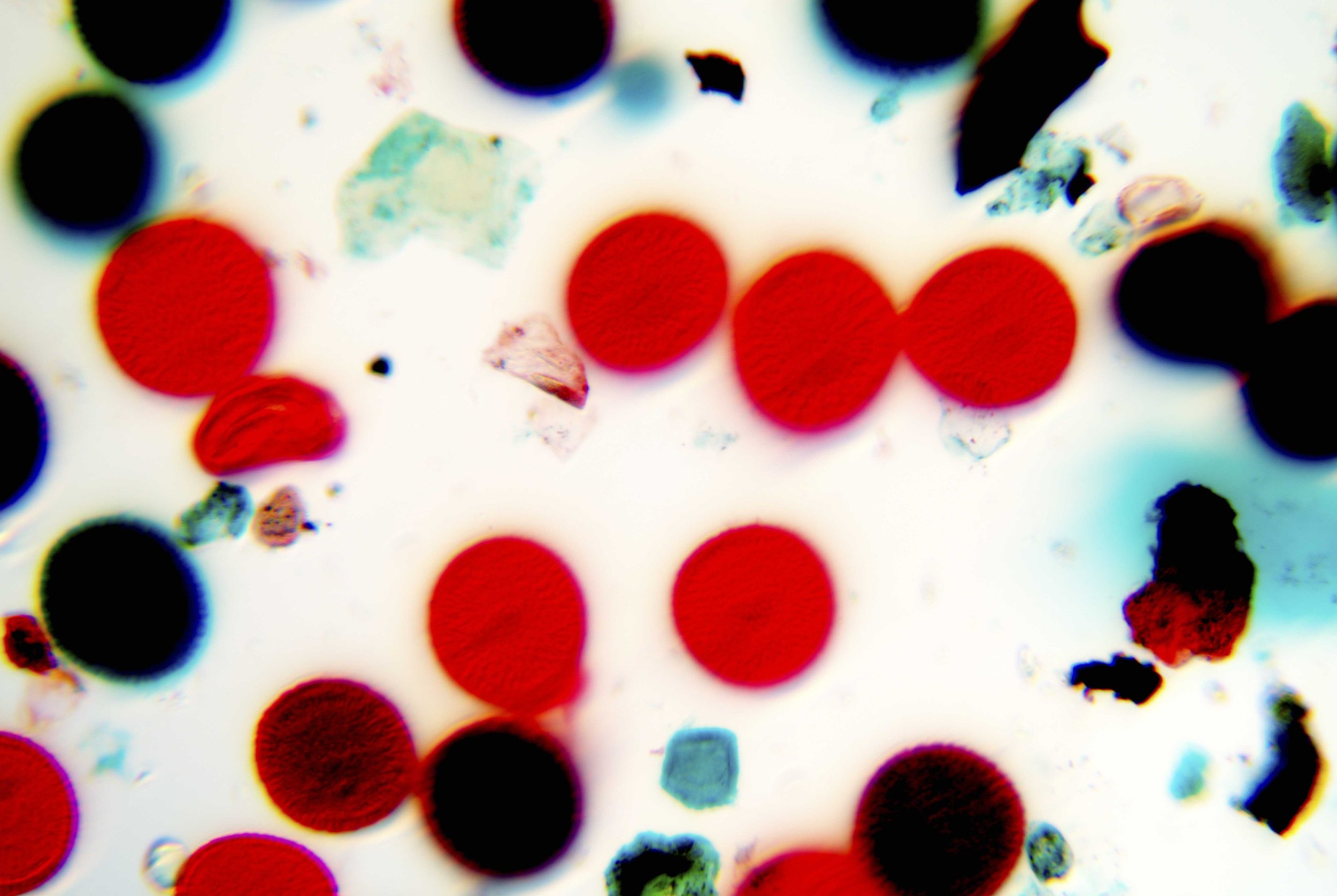

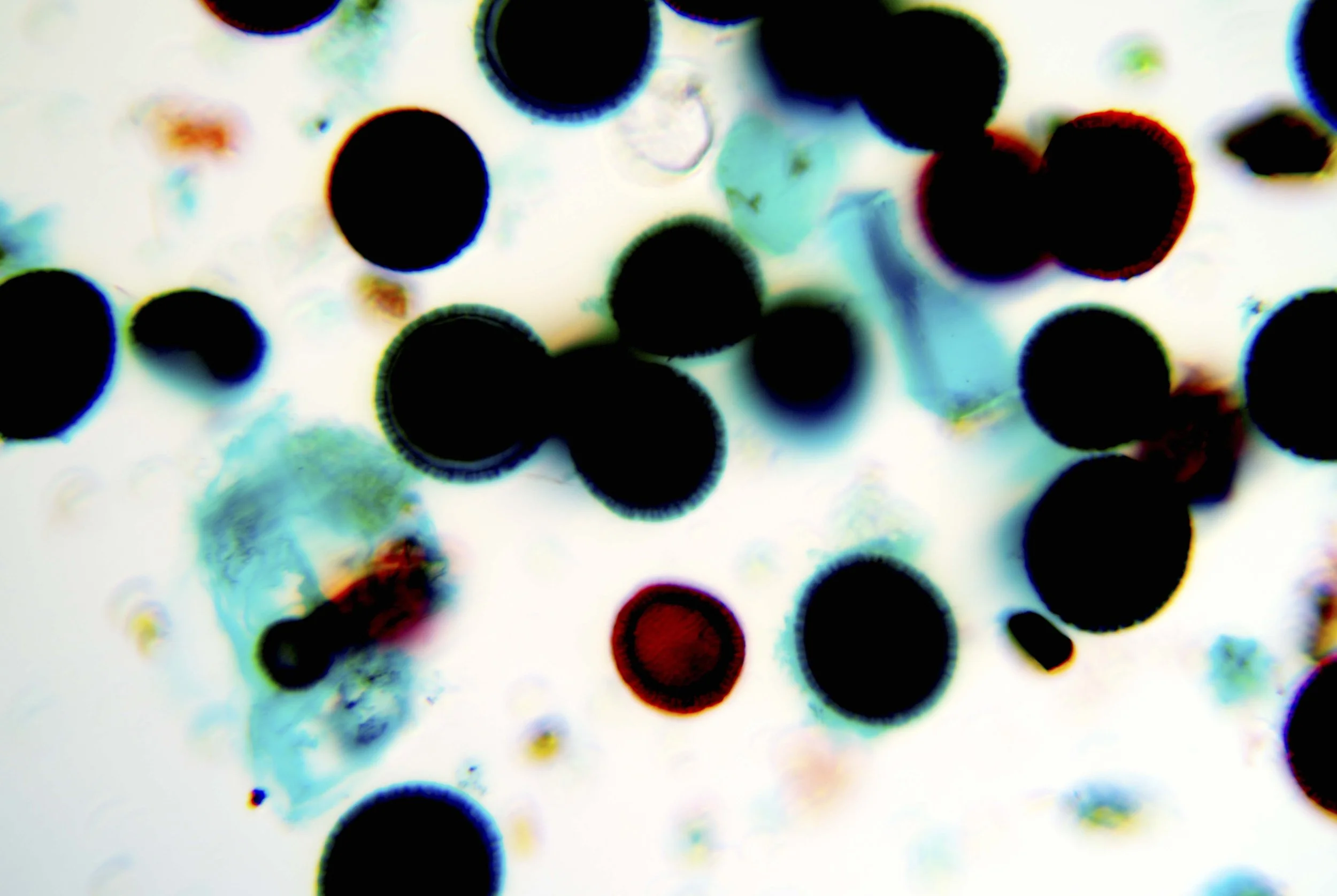

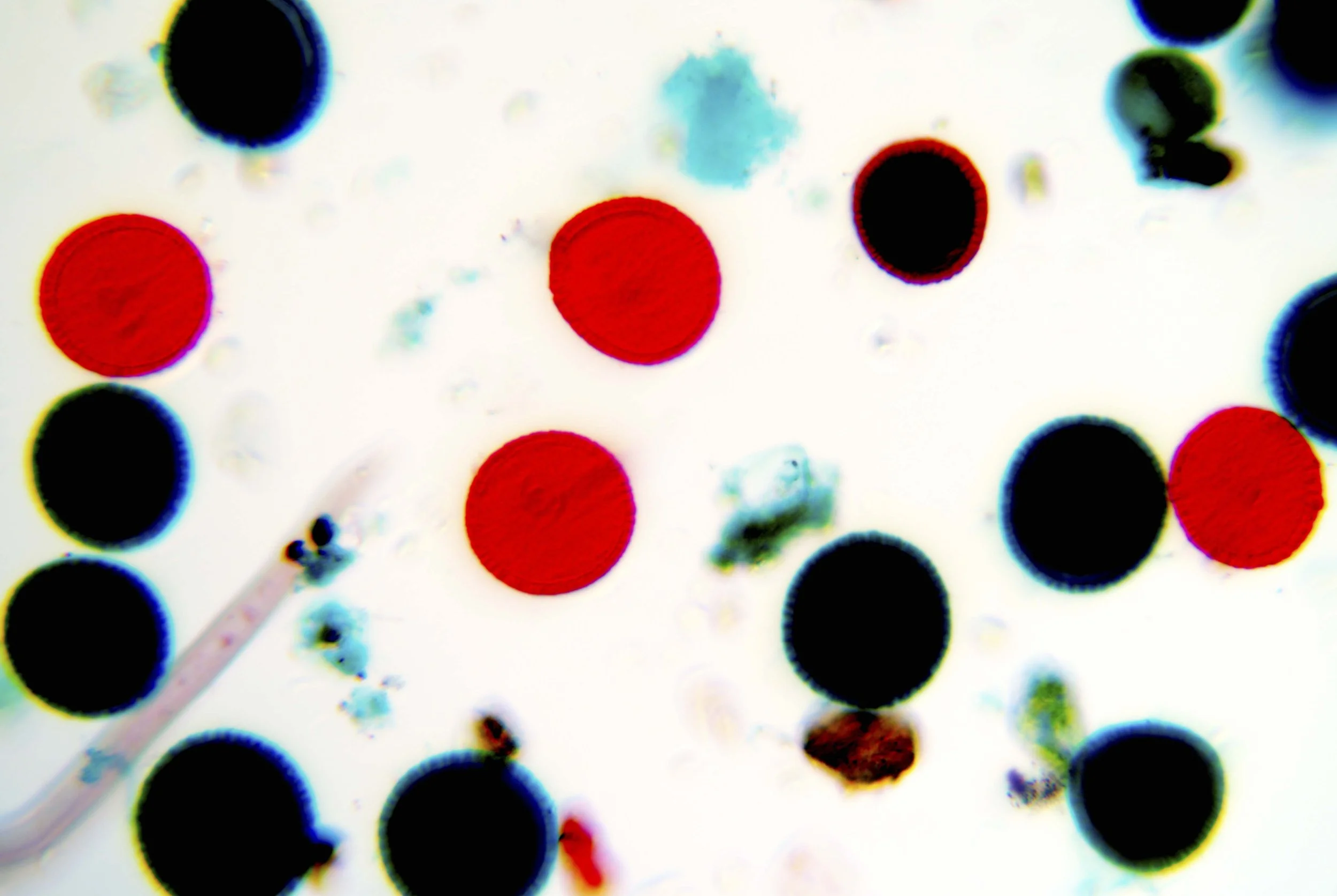

In magnified view, this resilience and diversity become strikingly visible. Some grains appear as deep black or midnight blue spheres, light absorbed by their dense exine walls, while others glow in shades of vivid red, their textured surfaces catching illumination in a way that makes them appear almost metallic.

These grain colors in microscopy often arise from staining, refractive differences, or interactions with polarized light, but the structural beauty is wholly natural.

Up close, the familiar world shifts into something new. These pollen grains resemble painted beads, distant planets, or molecular jewels. They dance across the microscope’s field like confetti scattered through water or pigments suspended in air.

Their forms tell stories of evolution, of co-adaptation between flowers and pollinators, and of the delicate, invisible exchanges that sustain life on Earth.